Directed Energy Weapons: The Hidden Defensive Role of Lighthouses

Were lighthouses only used for navigation, or did they also have a defensive mode as a directed energy weapon which has been kept secret?

The Starfire Codes produces an audience-supported publication with a stellar podcast, consciousness-expanding daily spiritual content, and well-researched articles on forbidden but crucial topics.

If you love our work, please join our constellation of curious minds and venture into forbidden realms of knowledge.

Hit that like button!

Share with fellow seekers!

If you haven’t yet, please become a Paid Subscriber to support the cosmic quest for truth!

This is what we do full time. Thank you for all of the ways you support The Starfire Codes! It means the universe to us.🌟

Click here to find out more about booking a personal divination reading, having a dream interpreted, purchasing a natal astrology report, and more….

Lighthouses have been protecting mariners for centuries by guiding the ships away from dangerous rocks and shoals. Their bright beacons break through the darkness, aiding in navigation and preventing countless shipwrecks. Yet there are also suggestions that these structures may have served a more sinister defensive purpose; they could use their powerful lenses not only to illuminate, but also to set enemy ships on fire.

The idea that lighthouses may have actually been used offensively first came up during the early 19th century. At that time, tales were told among British sailors of French lighthouse keepers located across the English Channel who sometimes aimed concentrated light beams from their Fresnel lenses at approaching British ships with such effect that sails burst into flames. Apparently, this was quite common during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) when Britain and France were enemies on the sea.

For years, historians dismissed these accounts as imaginative stories that had arisen due to war-induced nationalism and Francophobia. Modern analysis however has given some weight to such burning claims. Early lighthouse lens systems, which were called catoptric systems, made use of mirrored glass and polished silver reflectors to amplify and project light with sufficient intensity to ignite combustible materials. The very first Fresnel lens, manufactured in 1823, was even more potent; it could concentrate light from whale-oil lamps into an intense beam.

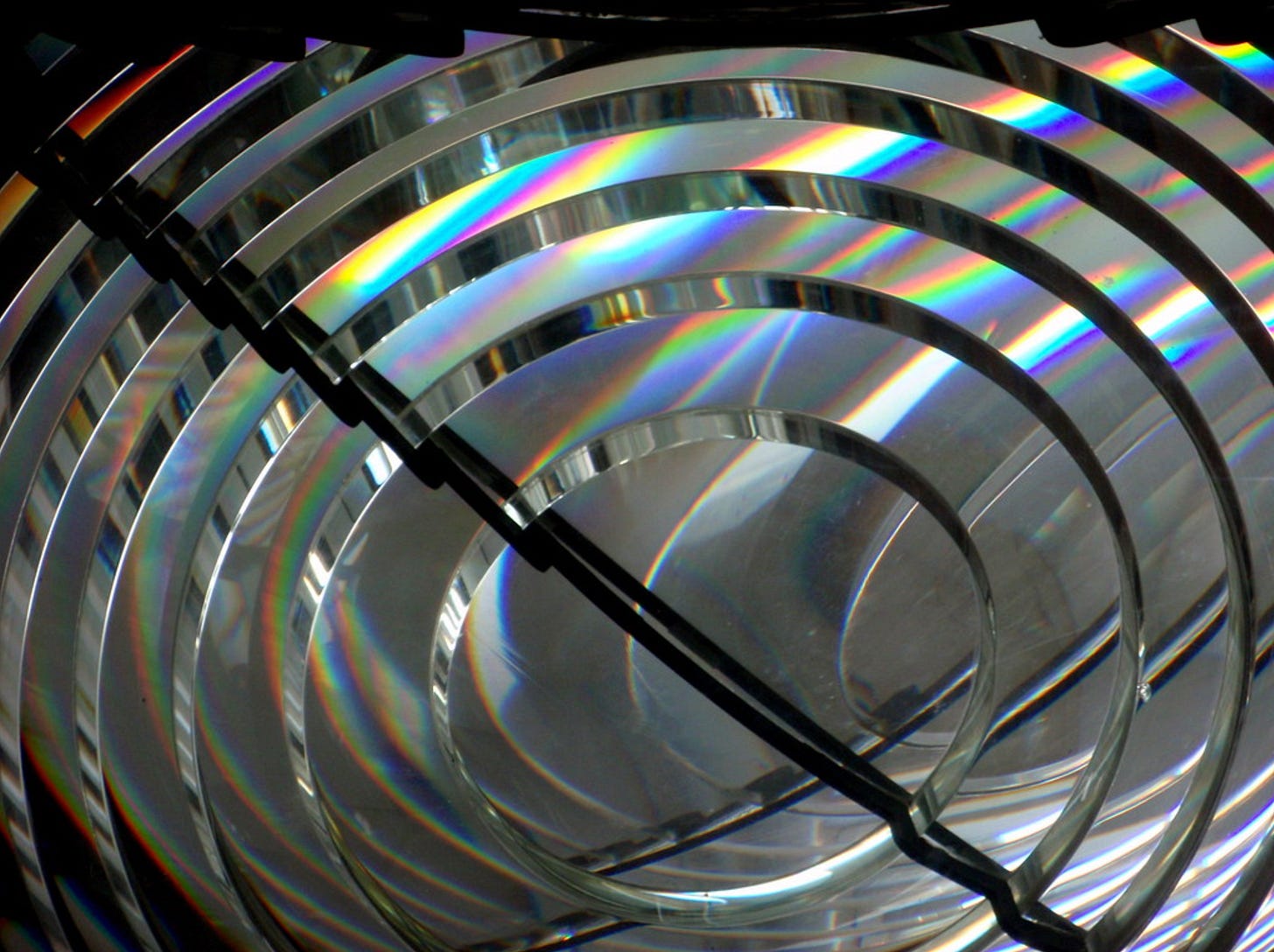

The prismatic lens, designed by French scientist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, made illumination from a lighthouse visible at far distances. But its parabolic glass panels and bulls-eye configuration could have easily made it a weapon of light capable of being used tactically as well. By slightly changing the lens’s position, its scorching focal point could be moved onto approaching sails at relatively close range.

This defensive theory gained more solid evidentiary support in 2005, when a handwritten memoir from an early 19th century French lighthouse keeper surfaced at an auction in Lyon, France. In the memoir, the keeper plainly admits to using his lighthouse's Fresnel lens to set fire to sails of British ships that drew too close to the French coast, usually by "mistake." He describes waiting until the vessels were within a few hundred meters before angling the light to ignite the rigging. And he notes proudly that this tactic saved his lighthouse from capture or bombardment by the British on at least two occasions during the Napoleonic Wars.

Some experts have questioned the authenticity of the lighthouse keeper's confession. But its descriptions do closely match the capabilities of early Fresnel lenses. Since a lighthouse beam diverges only slightly over distance, it's quite plausible that a Fresnel lens could ignite sails at ranges of 100-200 meters. And the tactical use described would have required only subtle realignment of the lens, not wholesale movement of the entire lamp assembly.

The fiery tactic may have been ramped up even further with later lighthouse upgrades. When more powerful oil lamps replaced whale-oil lanterns in the mid-1800s, the lenses' illumination doubled in intensity. The lamp wicks were also set on mechanical clockwork devices that rotated the light in a sweeping beam pattern, potentially making it even easier to direct the brightest focal point outward. Some lighthouses even used magnesium flares that burned with enough searing heat to instantly ignite sails from a kilometer away.

Of course, we have no direct evidence that French lighthouse keepers actually used these enhancements as directed energy weapons against British ships. Aside from the memoir, there are no known eyewitness accounts of such a burning attack taking place. Some naval historians thus conclude that stories of fiery lighthouse lenses were likely exaggerated, their defensive role more myth than reality.

But others argue that, while specific cases are unconfirmed, the capability certainly existed. They point to the documented history of lighthouses being frequently attacked, captured, and destroyed during wartime by enemy ships. Clearly, lighthouses were considered prime strategic assets worth fighting over. So it stands to reason that at least some keepers would have been willing to use their powerful lenses as an improvised means of protection or retaliation when their towers were threatened.

And burning lenses could have served as an effective deterrent. Knowing that a lighthouse keeper could ignite their ships from a distance may have made some captains think twice before attacking or seizing towers manned by the enemy. The presence of such a devastating defensive capability, even if unused, may have warded off all but the most determined assaults. So in that sense, fiery lenses could have protected lighthouses without even needing to be turned directly against specific ships.

The debate continues among scholars, but compelling evidence and logic lend credibility to the possibility of tactical burning lenses. Their feasibility has even been demonstrated in modern experiments using replica Fresnel lenses. One such recreation managed to ignite paper sails from 100 meters when a lens was carefully aimed. So while hidden in the fog of history, the fiery truth may still shine through. Lighthouses likely did play a defensive role at times, using the very light that warned mariners away to also ward off attacking ships. Far from just a picturesque beacon, the focused beam from a Fresnel lens could have proven a potent 19th century defensive weapon when trained directly at an adversary.

The Burning Properties of Fresnel Lenses

At the heart of the fiery lighthouse theory lies the Fresnel lens, an ingenious device capable of concentrating sunlight and lamp light into a deadly beam. Invented in 1820 by French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, these prismatic lenses revolutionized lighthouse illumination, allowing lamp light to be visible over unprecedented distances. But they also had incendiary potential that may have been utilized as a tactical weapon against approaching ships.

Fresnel lenses enhanced lighthouse illumination by using carefully calculated prisms and reflectors to capture nearly all light from a lamp and direct it into a tight, virtually parallel beam. To mold the light this way, Fresnel divided the lens into concentric annular sections, each with prism ring oriented for proper refraction. The prisms collapsed the beam's divergence, while curved reflectors minimized stray light loss.

This optical arrangement created a very narrow light cone of just a few degrees divergence. It's why Fresnel lenses could cast a lighthouse beam 20-30 nautical miles, compared to just 5-10 miles for previous reflector systems. Light captured from all angles was efficiently concentrated into one brilliant beam.

But the lenses also focused this luminous energy into a blistering spot at their central focal point. Just beyond the lens, the light converges into a searing dot just a few inches across, with irradiance orders of magnitude higher than the wider beam. It's this intense hot spot that made Fresnel lenses such devastating solar burning glasses.

By shifting the lamp slightly off the lens's optical axis, the focal point could be redirected outward into the distance rather than onto the floor below. A lighthouse keeper potentially could have used this technique to shift the searing focal point onto an approaching ship's rigging at relatively close range. The concentrated irradiance would almost instantly ignite the sails and ropes.

Experiments have shown that early Fresnel lenses could ignite paper, wood, and other materials at distances of 100 meters or more, as long as the lamp was carefully aimed. The burning capabilities also increased along with enhancements in lens size and lamp power over the 19th century.

One key upgrade came in the 1860s with the use of funneled mineral oil lamps boosted by pressurized air. The "Lens Lights" produced up to 10 times more luminous output than previous colza or rapeseed oil lanterns. This allowed the beam to be visible from over 30 miles, but also multiplied the focal point's incendiary power.

Further intensification came from clockwork rotation mechanisms that swept the light beam in a pattern rather than leaving it fixed. The timed sweeping of the lamp across the lens significantly boosted the luminous intensity in the direction the lens faced. While intended to make the lighthouse more visible, this enhancement likely also focused the burning spot even more fiercely.

The piratical possibilities dawned on French engineer Leonor Fresnel even before he completed the first lens prototypes. In an 1819 letter, Fresnel speculated that his lenses could be used as "terrible weapons of war" by focusing sunlight on enemy ships and forts. The destructive applications seemed obvious, even if contrary to Fresnel's benevolent aims.

So while perhaps exploited only sporadically and unofficially, the incendiary potential of Fresnel lenses made their wartime use as burning glasses quite plausible. The beams that made lighthouses navigational beacons may have also served on occasion as ship-scorching rays, whether accidentally or intentionally. It was a latent function waiting to be unleashed when hostile ships encroached too close upon strategically vital towers.